Content by: Wikipedia

The Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 were a series of shark attacks along the coast of New Jersey between July 1 and July 12, 1916, in which four people were killed and one injured. Since 1916, scholars have debated which shark species was responsible and the number of animals involved, with the great white shark and the bull shark most frequently being blamed. The attacks occurred during a deadly summer heat wave and polio epidemic in the Northeastern United States that drove thousands of people to the seaside resorts of the Jersey Shore. Shark attacks on the Atlantic Coast of the United States outside the semitropical states of Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas were rare, but scholars believe that the increased presence of sharks and humans in the water led to the attacks in 1916.

Local and national reaction to the attacks involved a wave of panic that led to shark hunts aimed at eradicating the population of “man-eating” sharks and protecting the economies of New Jersey’s seaside communities. Resort towns enclosed their public beaches with steel nets to protect swimmers. Scientific knowledge about sharks before 1916 was based on conjecture and speculation. The attacks forced ichthyologists to reassess common beliefs about the abilities of sharks and the nature of shark attacks.

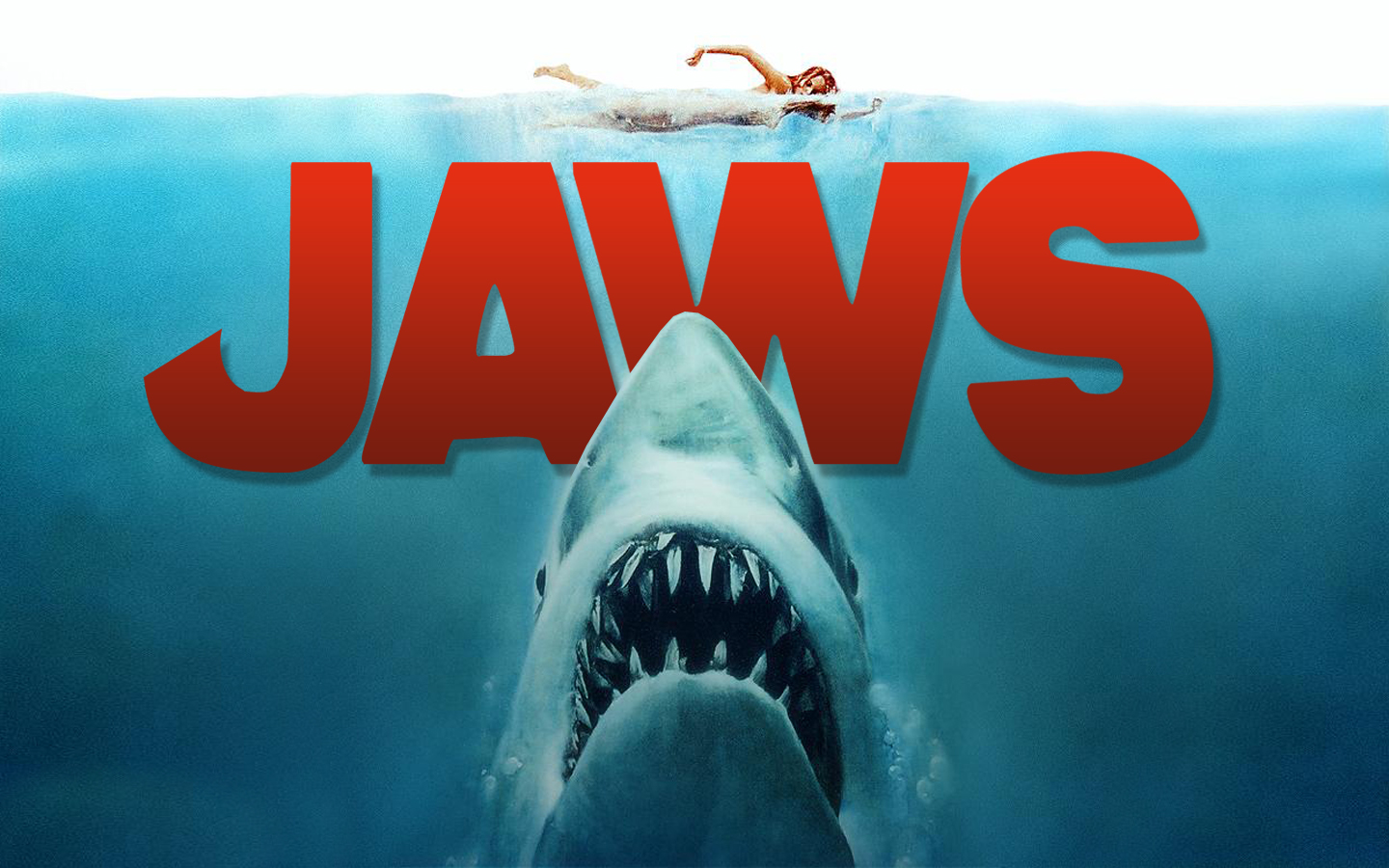

The Jersey Shore attacks immediately entered into American popular culture, where sharks became caricatures in editorial cartoons representing danger. The attacks inspired Peter Benchley‘s 1974 novel Jaws, an account of a great white shark that torments the fictional coastal community of Amity on New York’s Long Island, and the novel was made into the influential film in 1975 by Steven Spielberg. The attacks also became the subject of documentaries for the History Channel, National Geographic Channel, and Discovery Channel, including the film12 Days of Terror (2004) and the Shark Week episode Blood in the Water (2009

Attacks and victims

Between July 1 and July 12, 1916, five people were attacked along the coast of New Jersey by sharks; only one of the victims survived. The first attack occurred on Saturday, July 1 at Beach Haven, a resort town established on Long Beach Island off the southern coast of New Jersey. Charles Epting Vansant, 25, of Philadelphia was on vacation at the Engleside Hotel with his family. Before dinner, Vansant decided to take a quick swim in the Atlantic with a Chesapeake Bay Retriever that was playing on the beach. Shortly after entering the water, Vansant began shouting. Bathers believed he was calling to the dog, but a shark was actually biting Vansant’s legs. He was rescued by lifeguard Alexander Ott, and bystander Sheridan Taylor who claimed the shark followed him to shore as they pulled the bleeding Vansant from the water. Vansant’s left thigh was stripped of its flesh; he bled to death on the manager’s desk of the Engleside Hotel at 6:45. p.m.

Despite the Vansant incident, beaches along the Jersey Shore remained open. Sightings of large sharks swarming off the coast of New Jersey were reported by sea captains entering the ports of Newark and New York City but were dismissed. The second attack occurred 45 miles (72 km) north of Beach Haven at the resort town of Spring Lake, New Jersey. The victim was Charles Bruder, 27, a Swiss bellhop at the Essex & Sussex Hotel. Bruder was killed on Thursday, July 6, 1916, while swimming 130 yards (120 m) from shore. A shark bit him in the abdomen and severed his legs; Bruder’s blood turned the water red. After hearing screams, a woman notified two lifeguards that a canoe with a red hull had capsized and was floating just at the water’s surface. Lifeguards Chris Anderson and George White rowed to Bruder in a lifeboat and realized he had been bitten by a shark. They pulled him from the water, but he bled to death on the way to shore. According to The New York Times, “women [were] panic-stricken [and fainted] as [Bruder’s] mutilated body … [was] brought ashore.” Guests and workers at the Essex & Sussex and neighboring hotels raised money for Bruder’s mother in Switzerland.

The next two attacks took place in Matawan Creek near the town of Keyport on Wednesday, July 12. Located 30 miles (48 km) north of Spring Lake and inland of Raritan Bay, Matawan resembled a Midwestern town rather than an Atlantic beach resort.[4] Matawan’s location made it an unlikely site for shark attacks. When Thomas Cottrell, a sea captain and Matawan resident, spotted an 8 ft (2.40m) long shark in the creek, the town dismissed him. Around 2:00 p.m. local boys, including epileptic Lester Stillwell, 11, were playing in the creek at an area called the Wyckoff dock when they saw what appeared to be an “old black weather-beaten board or a weathered log.” A dorsal fin appeared in the water and the boys realized it was a shark. Before Stillwell could climb from the creek, the shark attacked him and pulled him underwater.

The boys ran to town for help, and several men, including local businessman Watson Stanley Fisher, 24, came to investigate. Fisher and others dived into the creek to find Stillwell’s body, believing him to have suffered a seizure; Fisher was also attacked by the shark in front of the townspeople. He was pulled from the creek without recovering Stillwell’s body. His right thigh was severely injured and he bled to death at Monmouth Memorial Hospital in Long Branch at 5:30 p.m.Stillwell’s body was recovered 150 feet (46 m) upstream from the Wyckoff dock on July 14.

The fifth and final victim, Joseph Dunn, 14, of New York City was attacked a half-mile from the Wyckoff dock nearly 30 minutes after the attacks on Stillwell and Fisher. The shark bit his left leg, but Dunn was rescued by his brother and friend after a vicious tug-of-war battle with the shark. Joseph Dunn was taken to Saint Peter’s University Hospital in New Brunswick; he recovered from the attack and was released on September 15, 1916.